Why exporters do better

Exporters tend to perform better than non-exporters for several reasons: They specialize their production and enjoy economies of scale; they interact with, and learn from, foreign consumers and suppliers; and they face stronger competitive pressure that prompts them to make investments and improve their business practices.

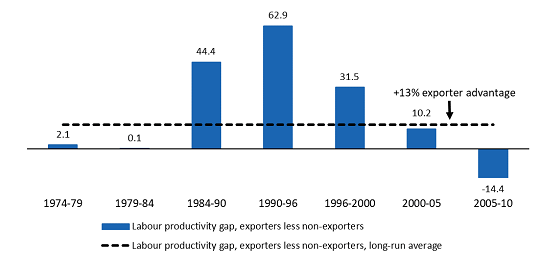

Extensive research on Canada’s manufacturing sector finds that exporters produced 13% more output per worker than non-exporters on average from 1974 to 2010. The evidence suggests that exporting helps improve the performance of individual companies, but also translates into noticeable benefits for the overall economy. In general, the more intensely Canada exports, the higher is its overall productivity.

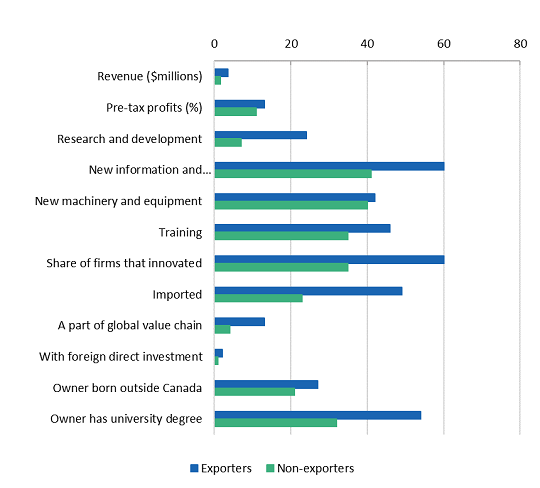

Exporters tend to be more innovative. For instance, between 2004 and 2009, exporters reported roughly twice as much research and development (R&D) activities as non-exporters.

New exporters typically enjoy the largest benefits. But as a company’s global connectedness increases, so too does its cumulative performance improvement in terms of output, employment, and investment in physical, human and R&D capital.

Although large companies are more likely to export, and export more than smaller firms, there are also significant benefits for small- and medium-sized enterprise (SME) exporters. For example, in 2011, SME exporters had higher revenues and profit margins, and did better along a wide range of performance metrics.

Exporters outsized and growing contribution

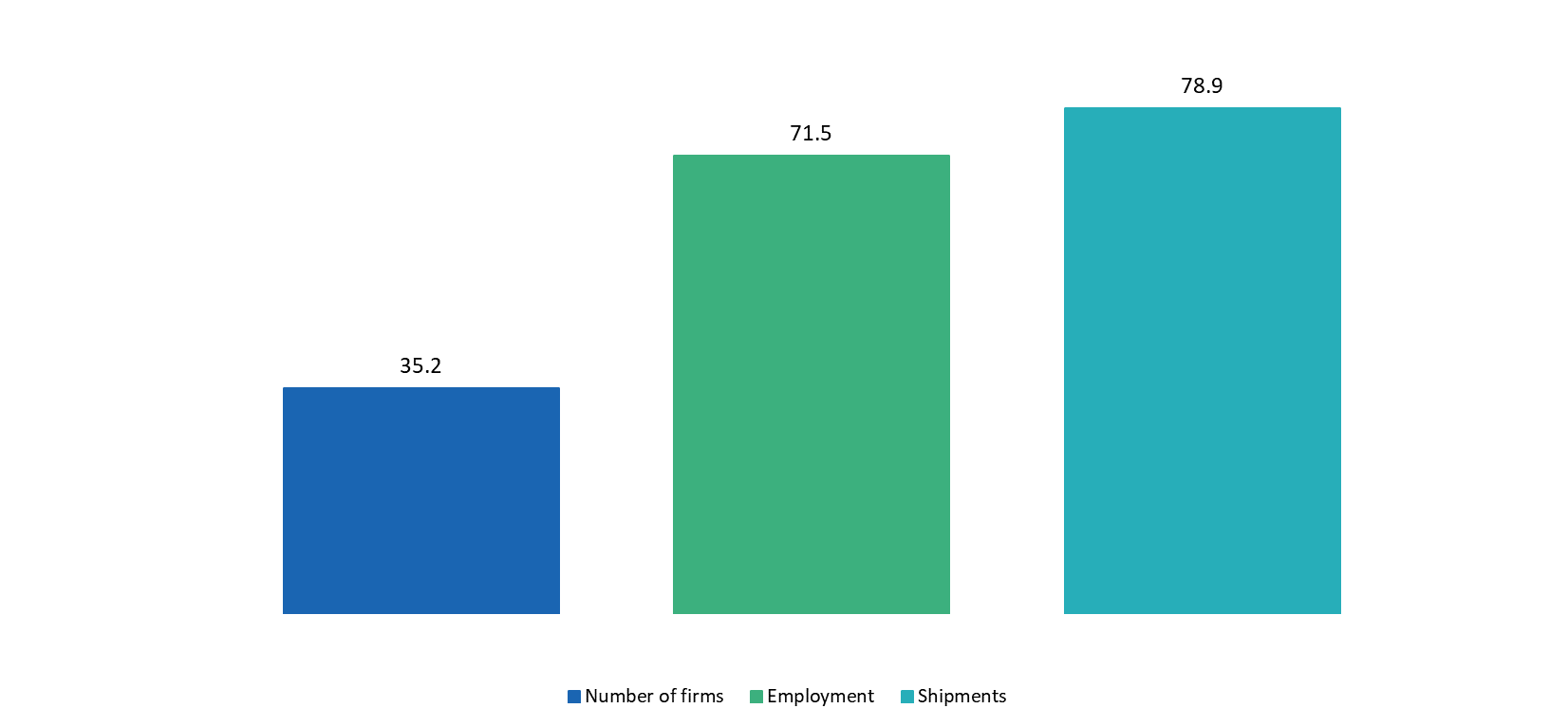

Research shows that Canadian exporters make an outsized contribution to overall economic activity. Between 1974 and 2010, the 35% of Canadian manufacturing firms that were exporters accounted for more than 70% of overall manufacturing employment and shipments.

Export shares, Canadian manufacturing firms, average 1974 to 2010 (per cent of total)

Source: Baldwin and Yan (2015)

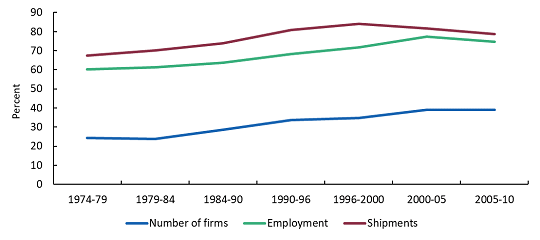

The importance of exporters to the economy has grown over time. In the 1970s, less than one-quarter of Canadian manufacturers exported. This share grew to 39% in the 2000s, during which exporters’ contributions to employment and shipments also increased–from around 60% in the 1970s to nearly 80% in the 2000s.

Export shares, Canadian manufacturing firms, 1974 to 2010 (per cent of total)

Not only are more Canadian companies exporting, but export intensity (i.e., the share of total sales that are generated abroad) has also risen over time —from 28% of total sales in the 1970s to more than 40% in the 2000s.

Exporter performance benefits

Productivity is a key economic performance indicator that measures how efficiently a firm uses its inputs to produce outputs. The labour productivity (output per worker) of exporters was 13% higher on average than that of non-exporters in Canada’s manufacturing sector from 1974 to 2010.

Labour productivity gap, exporters less non-exporters, Canadian manufacturing firms, 1974 to 2010 (per cent difference)

While performance gaps have typically favoured exporters, they change over time as the economy experiences tariff changes, exchange rate movements and other factors that affect productivity performance.

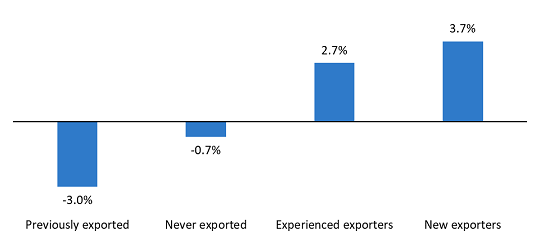

In the 1980s and early 1990s, Canada’s trading environment was more favourable due to global tariff reductions, the introduction of the Canada-U.S. Free Trade Agreement (CUSFTA, subsequently NAFTA), and a general depreciation of the Canadian dollar. In such a context, exporters’ productivity improved substantially, increasing from near-equivalence with non-exporters in the early 1980s recession to being over 60% more productive by the mid-1990s. Estimates suggest that American tariff cuts under the CUSFTA raised labour productivity at the plant level by 1.9% annually in the most affected export-oriented manufacturing industries in Canada. Furthermore, between 1990 and 1996, exporters—both old and new, but particularly new exporters—had much higher productivity growth than non-exporters.

Labour productivity growth by export status, 1990 to 1996 (per cent annual growth)

These dramatic differences were unwound after 2000 as the trading environment worsened for Canadian firms due to a “thickening” of the Canada-U.S. border associated with tighter security measures after 9/11, and an appreciating Canadian dollar during a commodity price boom. In fact, during the period covered by the global recession in 2008 and 2009, the productivity performance of Canadian exporters deteriorated–as a result of having significant excess capacity–and became 14% less productive than non-exporters, which is a historical anomaly.

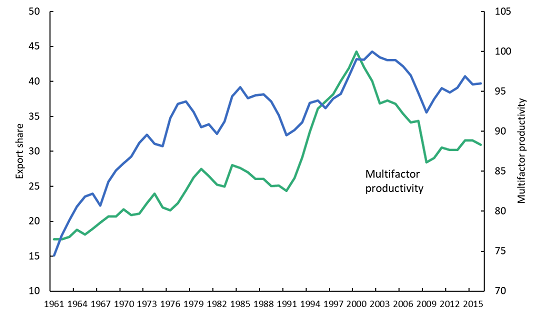

The evidence suggests that exporting is important for the performance of individual companies, and this translates into noticeable benefits for the overall Canadian economy. For instance, Canada’s export share of the economy and its business sector productivity have tracked each other quite closely for more than half a century since 1961. In general, the more intensely Canada exports, the higher is its overall productivity.

Export share and multifactor productivity, Canadian business sector, 1961 to 2017

Source: Authors’ calculations based on Statistics Canada, CANSIM database, tables 380-0064 and 383-0021. Note: Export share equals exports relative to gross domestic product (GDP), all in current dollars. Multifactor productivity is the ratio of real GDP to combined labour and capital inputs (base year 2002=100).

Improved information flows

Interactions with foreign buyers are one important channel that benefits exporters. This process helps to facilitate adoption of international best practices and transfer knowledge from foreign sources to Canadian firms. Upon entering export markets, new exporters become 37% more likely to use foreign technologies than non-exporters. They become more likely to collaborate on R&D with foreign buyers and less likely to view the lack of information on foreign technologies as a significant impediment to their use.

Gains from the scale and specialization

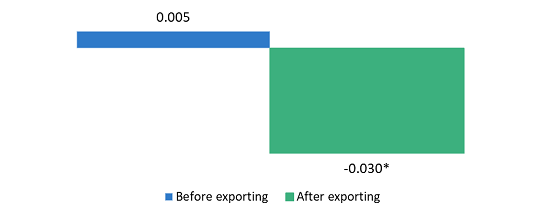

Access to global markets permits exporters the opportunity to specialize their product lines and exploit economies of scale, which in turn reduces average production costs and raises productivity. Prior to exporting, exporters offer a similar range of products as non-exporters. However, as companies start their exporting journey, they become more specialized than non-exporters.

Difference in product diversification index, exporters less non-exporters, Canadian manufacturing sector, 1990 to 1993

Note: * signifies statistically significance difference at the 1% confidence level.

Intensified competitive pressure

Stronger international competition forces exporters to become more efficient. New exporters indicated a significant rise in foreign competition relative to non-exporters. Prior to exporting, there’s no significant difference in the ranking of international competition facing exporters and non-exporters. After exporting, however, exporters have a seven percentage point higher likelihood than non-exporters to rank foreign competition as “very or extremely significant.”

Stronger incentives to invest and innovate

Exporting sharpens firms’ incentives to invest and innovate because access to larger markets provides a larger return on a given investment. In addition, innovative capabilities are enhanced as new exporters invest in R&D and training to develop the ability to absorb and incorporate foreign ideas and technologies.

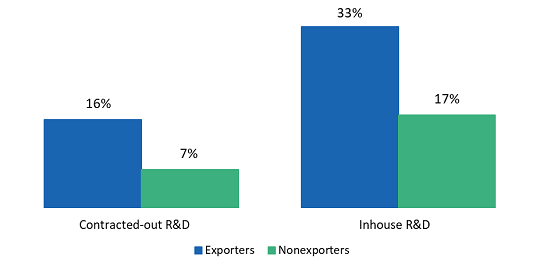

Exporters invest more in R&D. Between 2004 and 2009, about one-third of exporters conducted scientific R&D in-house (which qualifies for tax deductions because of its originality and is often directed at developing path-breaking new products and processes), while 16% contracted it out. This was roughly double the R&D activities reported for non-exporters of (17% and 7%, respectively).

Research and development shares, Canadian manufacturing firms, 2004 to 2009

Exporters also invest more in employee training than non-exporters. Larger plants that became exporters increased their emphasis on training as a general strategy, while they shared similar strategies as non-exporters before exporting.

In fact, exporters who invest and innovate are the ones that benefit the most. New exporters who experienced labour productivity gains were those who adopted advanced technologies and engaged in product innovation more frequently than did non-exporters. In contrast, there was no difference in technology adoption and product innovation between non-exporters and new exporters who didn’t experience labour productivity gains.

Continual process improvements

Over time, firms that move into new markets undergo dynamic transformations in their production processes. This is particularly true for exporters that are fully integrated into global value chains (GVCs) by becoming two-way traders that, not only export, but also import intermediate goods. Baldwin and Yan found that roughly 60% of exporters in the Canadian manufacturing sector were involved in this type of two-way GVC trade.

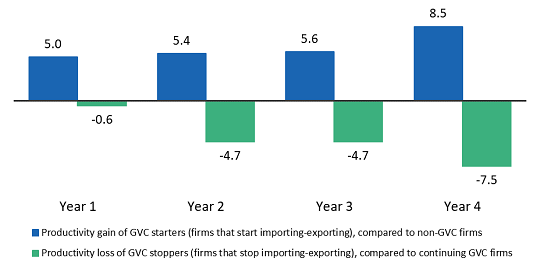

Between 2002 and 2006, the group of firms that started importing and exporting experienced 5% faster productivity growth in the first year than the group of non-GVC traders, and this advantage continued to grow, reaching 9% after four years. Conversely, firms that stopped participating in GVCs fared worse than the continuing GVC group. Their performance declined from -1% slower productivity growth to -8% four years later.

Productivity growth difference, Canadian manufacturing sector, 2002 to 2006

Note: GVC = global value chain firm

A related recent study (Baldwin and Yan, forthcoming) shows that the sustained superior performance over a longer time horizon for the group of GVC exporters is associated with continuous skill-upgrading of the workforce. Greater global integration is accompanied by a dynamic learning process that involves innovation and organizational changes in terms of capital intensity, skill acquisition and research spending. As the global connectedness of firms increases, so does their cumulative improved performance in terms of output, employment, and investment in physical, human and R&D capital.

Benefits for all firm sizes

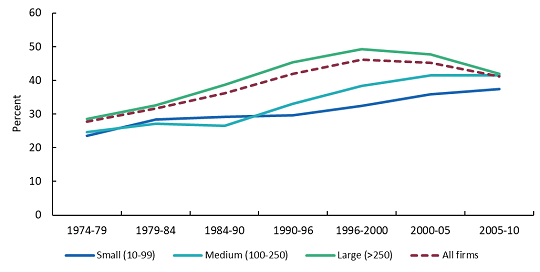

Large firms are more likely to export, and export more, than smaller firms. In Canada’s manufacturing sector, small-scale companies (those with less than 100 employees) exported 33% of their total shipments, compared with 37% for medium-sized firms (that employed between 100 and 250 people) and 43% for large firms (with more than 250 employees) between 1974 and 2010.

Over time, firms of all sizes have intensified their export activity, but particularly medium-sized firms, whose export intensity caught up to that of large firms by 2010.

Export intensity of Canadian manufacturing firms, by firm size, 1974 to 2010

Note: Export intensity=export share of total shipments.

In this regard, medium-sized firms have demonstrated similar export capacity to large-scale firms. Smaller firms can face considerable challenges in accessing high-value and specialized knowledge, incorporating such knowledge into their operations and accessing the financing needed to make and sustain major investments. This matters to growing Canada’s exporting capacity because the majority of Canadian companies (98%) are small-scale.

Those SMEs that overcome these barriers to become exporters enjoy similar benefits, as described above. For example, in 2011, SME exporters had higher revenues and profits and invested more in R&D, machinery and equipment, and training than non-exporting SMEs. They were also more innovative and more involved in other international activities, such as importing, outsourcing and transacting with, or as part of, GVCs. As well, the owners of exporting SMEs were more likely to be born outside Canada and to have higher levels of formal education than Canadian-born owners.

Characteristics of SME exporters and non-exporters, Canada, 2011