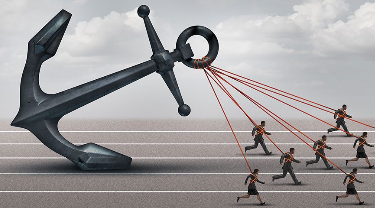

Trade barriers. They can be challenging, but not insurmountable when exporting to a new market.

Aside from the obvious tariff barriers—a duty on imported goods—there are an array of non-tariff barriers that can act as obstacles to exporting. Product quotas and licensing, customs clearances, certification standards, entry taxes as well as language and culture, all of which can all are classified as non-tariff barriers.

While trade barriers hinder trade, free trade agreements (FTAs) eliminate most barriers and create new opportunities. While tariff elimination may be the main goal, agreements can extend into other areas and cover non-tariff barriers including quotas, product standards, labour and intellectual property.

Canada has 11 FTA agreements with 15 countries, including the European Free Trade Association (EFTA), a goods-only agreement with an emphasis on tariff-elimination that includes the countries of Iceland, Liechtenstein, Norway and Switzerland.

The good news for Canadian exporters is that starting this September, the Canada-EU Comprehensive and Economic and Trade Agreement (CETA) will be provisionally applied, opening up a market of more than 500 million people to Canadian companies in Europe.

When CETA is provisionally implemented, it will reduce tariff barriers, approximately 98 per cent of all tariffs immediately, in 28 EU markets including the UK until Brexit comes into effect in March 2019. The EFTA also reduces barriers in four OECD European nations.

Despite CETA and the EFTA, Canadian companies looking for new customers in Europe will face some form of trade barriers.

“There are barriers to any market,” says Trade Lawyer Mark Warner who previously practiced law in Brussels. “That’s why it’s crucial as a first step, to do your homework.”

Namely, companies need to find out if going into a particular market makes economic sense.

“The biggest hurdle for Canadian SMEs is understanding market dynamics and who they are selling to,” adds Warner. “To me, that’s the biggest barrier to trade.”

Canadian companies often don’t possess strong linkages within supply chains in the European market. In many cases, small and medium-sized companies are Canadian companies just starting their export journey from scratch.

There are many options for breaking into a new market by establishing a local presence. The easiest way is to utilize the Internet or, for a strengthened local presence, companies can establish a bricks and mortar business by partnering with a local company through a joint venture or affiliate relationship.

Doing so bypasses many trade barriers. While requirements for establishing a business entity are increasingly formally the same for foreign firms and locally owned companies, there are often lingering rules that impose increased burdens on foreign-owned firms.

Bypassing trade barriers is only one of several benefits operating a local business can offer.

Depending upon the market, other advantages include:

- Increases sales and market share

- Ability to serve local customers better

- Improved access to supply chains and regional networks

- Lower labour and operating costs

- Reduction or elimination of legal and other regulatory barriers

- Better access to technology

“There are many ways of breaking into a new market; you have to figure out what makes the most sense for your particular business,” says Warner. “It’s not a one-size-fits-all proposition.”

If establishing a local presence doesn’t make sense, there are still other options including developing a relationship with a distributor and/or utilizing the expertise of a customs broker.

In markets where the customs process is slow and cumbersome, a distributor can help overcome potential trade barriers. Distributors buy a company’s product and sell it to their own customers in the specific market. The distributor handles the details of importing the product, specifically clearing customs and paying duties and taxes. They also deal with in-market logistics, which can be an important selling point if the local customs process is prone to delays.

Choosing the right agent abroad is one of the most important decisions a company can make when it is planning to enter a new market. Quebec’s Morgan Schaffer , as one example, deals with more than 150 international agents on a regular basis. It finds many at trade shows, through recommendations of customers, other agents and industry partners and sometimes even using a former competitor’s agents.

Good international agents can advise on local financing and transportation options, clear goods through customs, make collections and help you wind your way through local laws and customs.

The agent has to have integrity, good technical knowledge, engineers on staff, know the local industry and be ready to invest money and time for at least two years before seeing any return on his investment, according to Serge Gutieres, Sales and Marketing Director at Morgan Schaffer.

“It takes a minimum of two years to 30 months for us to develop and train a new agent, allow him to penetrate his market and start seeing real sales. In some markets, it takes close to four years,” he says.

One of the biggest barriers to entering a new market is culture and language.

“It is always a challenge to work with entrepreneurs in different countries and cultures. Communication is king. Language barriers and different business practices are the two main challenges. To manage that, you have to regularly visit your agents face-to-face to build relationships and trust, understand their market and customers yourself, and adapt your sales strategy,” says Gutiere.

A recent study by Toronto-based trade services firm Livingston International revealed that the number of businesses expected to use two or more trade agreements in the next 12-24 months is expected to increase by 63 per cent. Not surprisingly, the biggest growth in trade activity is expected to be with the EU.

As a result of CETA, 98 per cent of tariff barriers will eventually be removed beginning when the agreement is goes into effect provisionally, opening up a market of approximately 500 million. However, the agreement addresses more than tariff removal—over time, there will be mutual recognition of standards as well, developed in a regulatory co-operation framework.

“Products standards and testing is the big win in this deal,” says Audrey Ross, Logistics and Customs Specialist at Toronto’s Orchard International. “Establishing processes and testing centres in Canada saves time and money for Canadian businesses looking to export their products to the highly regulated EU market. As we move forward, standards will be reviewed and created jointly.”

While CETA is a great deal, it ignores the barrier of local taxes which in Europe, are much higher than Canadians are accustomed to, Ross adds.

In addition to the potential additional delivery costs, when goods are sold abroad they could be subject to an applicable value-added tax or a local sales tax. It is extremely important to understand the local country rules surrounding VAT and sales tax to ensure compliance.

“A few years ago, Orchard had a few small orders with European customers. We realized that if we wanted to grow our business we would need to learn more. We connected with a global tax firm who strongly recommended creating a presence in the Netherlands. We registered for a VAT (value added tax) number with the Dutch Tax Authorities and set up a Fiscal Representative,” she says. “Our tax firm recommended a Dutch freight forwarder. We import our goods through the Netherlands, clear customs, process VAT through a Fiscal Representative and then deliver to our new customers in France, Germany, the UK and Italy. We complete monthly, quarterly and annual tax filing to the Dutch Tax Authorities with the assistance of our tax consultant. It’s expensive to use consultants and it’s less expensive than paying VAT (17- 22 per cent depending on the member state) and we now have almost all of the advantages of a domestic importer.”

Bottom line concerning CETA

While CETA will unlock new doors of opportunity for Canadian companies, they have to be willing to seize the potential, says Warner.

“There’s a lot of great PR around how great the opportunity is,” he adds. “But the big issue is whether Canadian businesses become less risk averse and commit to entering new markets.”

International trade expert Jayson Myers concurs.

“What’s more of a concern than trade barriers is if Canadian companies are prepared to take advantage of the new opportunities CETA will provide,” he says. “It’s a very sophisticated market and the question is do companies have the technology and meet the standards to do business in the EU?”

Warner says that Canadian SMEs in particular must realize that selling to the EU is not the same as selling in Canada.

“It’s totally different market; what sells in North America necessarily won’t sell in the EU,” he says. “What is going to be difficult for SMEs, is that they will have to spend money to truly understand the market.”

Understanding the EU market starts with looking at customer demands, Myers adds.

“You have to make sure you appeal to customers that are looking for different things rather than thinking you have a product and are simply pushing it into a different market,” he says. “Most companies realize today that they have to customize their products and services to provide value to the customer in the new market—it’s the foundation of exporting in the new millennium.”

Elimination of trade barriers:

Trade barriers in the form of tariff and non-tariff barriers hinder trade. However, Free Trade Agreements (FTAs) eliminate barriers and create new opportunities. Tariff elimination may be the main goal, but agreements can extend into other areas and cover non-tariff barriers including quotas, product standards, labour and intellectual property.

CETA, once provisionally applied will reduce trade barriers around certification – one of the largest non-tariff barriers in EU countries.

CETA will allow Canadian producers to have certain products tested and certified, for EU markets, right here in Canada. This will reduce testing and certification costs and delays for manufacturers.

Reduce red tape:

Wherever possible, customs procedures will be simple, effective, clear and predictable so as to reduce processing times at the border and make the movement of goods cheaper, faster and more efficient.

EU trade barriers:

Eliminating barriers and creating new opportunities. Tariff elimination may be the main goal, but agreements can extend into other areas and cover non-tariff barriers including quotas, product standards, labour and intellectual property.