When the Comprehensive Economic and Trade Agreement (CETA) came into force in 2017, experts declared a new era of increased trade and economic opportunities for companies and workers in Canada and the European Union (EU). As we mark the third anniversary of the deal, there’s much to celebrate as bilateral trade has increased for goods and services. But to understand where we are now, it’s important to reflect on CETA’s benefits through reduced or eliminated tariffs.

CETA negotiations between Canada and the EU began in 2009 and provisionally came into force Sept. 21, 2017. It was heralded as a new era in trade for both Canada and the members of the EU. It was touted as a “comprehensive” agreement because it covers so much, from trade in goods and services to investment flows and the movement of people. It also recognizes the product standards and the professional certifications required by both Canada and the EU. While there are rules governing such issues, CETA has made it easier for all parties to accept these standards and certifications.

We’ve been impressed by the robust growth in bilateral Canada-EU trade observed since the trade deal provisionally came into force in 2017.

“CETA is a critically important trade agreement for Canadian companies, and comes along at a particularly opportune time, when market access in the major markets of the United States and China has become less predictable for certain sectors,” says Tapp.

Merchandise trade between Canada and the EU increased after the implementation of CETA. Exports from Canada to the EU grew by 21% from $40 billion in 2016 to $48 billion in 2019. Imports from Canada to the EU grew by 27% from $61 billion in 2016 to $77 billion in 2019. All told, the trade value increased by 25% during this period.

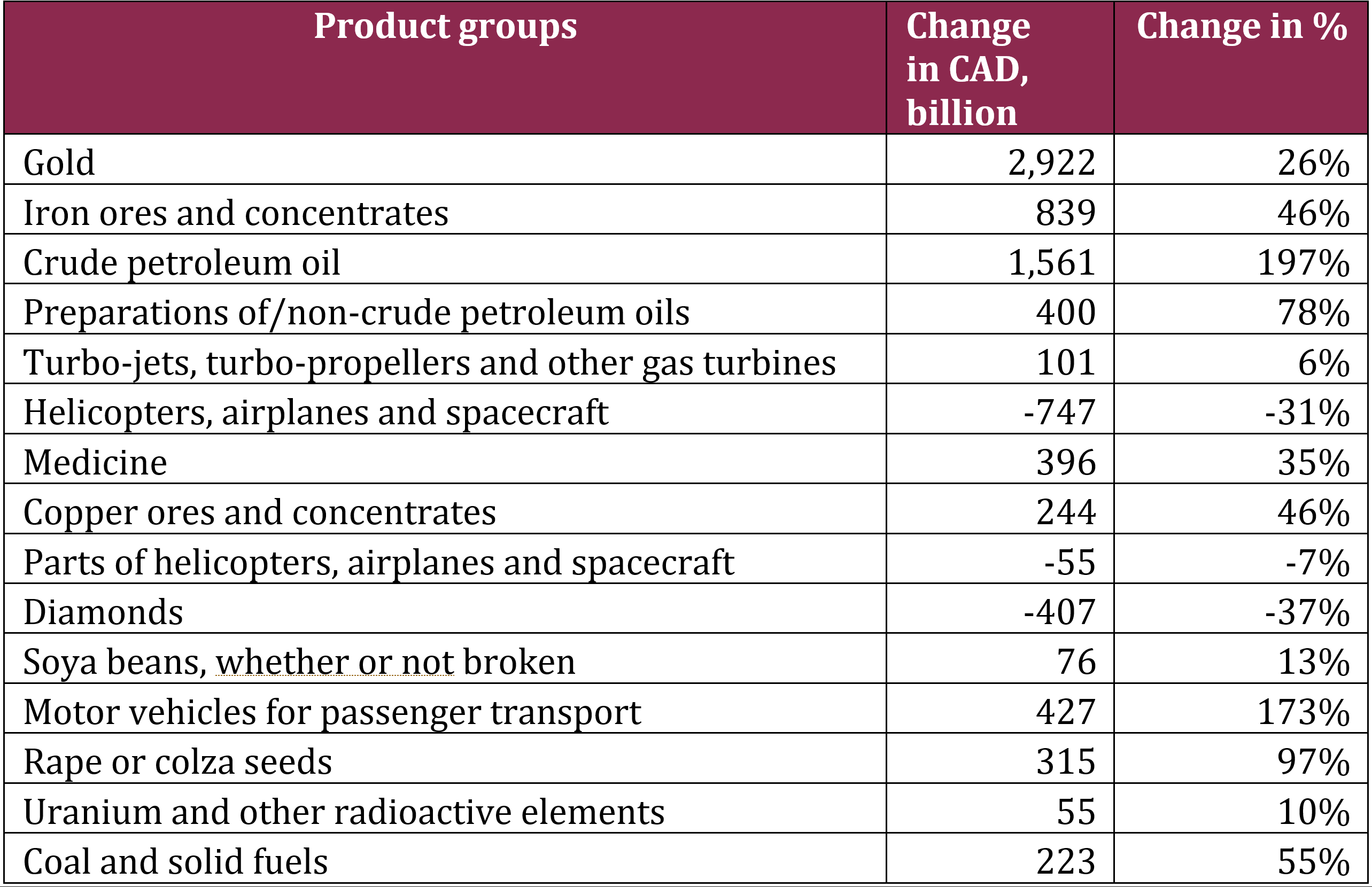

Canadian exports to the EU by product had varied performance. Product groups that performed well include metals, energy, motor vehicles and agriculture. Diamonds and aerospace performed poorly in the same period.

Changes to Top 15 Canadian exports to EU from 2016 to 2019

From an investment perspective, total foreign direct investment (FDI) in the EU by Canada increased by 16% from $262 billion in 2016 to $304 billion in 2019. Similarly, FDI made by the EU in Canada increased by 19% from $259 billion to $308 billion in the same period.

With CETA, the opportunities for Canadian companies to go global and diversify abroad are significant. That said, trade doesn’t increase merely because of an agreement: Canadian companies must still create strategies that will help them benefit from CETA’s potential. However, it must be noted that many Canadian businesses are also contending with enormous global trade uncertainty due to the global pandemic and supply chain and travel disruptions.

In order for Canadian exporters to receive the CETA preferential tariff rate, they require (rules of origin) documentations to prove that their goods originated from Canada. Only about half of all Canadian exporters (49.9% in 2018 and 53.1% in 2019) that are eligible are taking advantage of this—although this varies widely between different sectors.

Sectors such as zinc, sugar, and cereals have seen utilization rates near 100%. On the other hand, nickel, railway and parts, and copper are seeing CETA utilization rates in the single digits. The utilization rate of CETA preference for Canadian exports varies between different countries as well. It’s concerning that the larger European economies such as France, the United Kingdom and Germany all have utilization rates below average. While CETA is certainty benefitting Canada, the full potential of the trade deal is yet to be seen as the utilization rate of CETA preferences remains moderate.

For the most part, Canadian companies have enjoyed additional value to what they already sell in the EU. Tariffs on seafood, for example, are now minimal, a far cry from the 20% formerly applied to many Canadian seafood products. Earlier this year, tariffs on frozen lobster and frozen crab have been phased out. Tariffs on most seafood products will be fully phased out by 2024. It’s expected that there will be many more opportunities for Canadian food exporters as Europeans spend comparatively more of their household income on food than do Americans. As well, Canada’s strong international reputation in the agri-food sector continues to benefit our food products.

“There are several areas where Canadian companies can take advantage of CETA,” says Tapp. “In agriculture, Canadian companies directly compete with those from Brazil and the United States. CETA has provided Canada with a competitive boost in the world’s largest market for food and agricultural products.”

CETA has provided opportunities in other sectors as well, which include:

- High-tech manufacturing, such as electronic components, instrumentation and navigational equipment

- Building materials, lumber and paper products

- Industrial machinery and parts

- Metal products, chemicals and plastics

Thanks to CETA, Canadian companies gained access to EU materials, technology, intermediate inputs and skilled labour. Our exporters continue to take advantage of these resources to make their supply chains more competitive.

On the services side, there are opportunities in the consumer and business sectors. These include:

- Engineering, architectural and construction services

- Marine and ocean technology services

- Health care and education

- Software and information technology

- Mining and energy support services

- Management and administrative services

- Environmental services such as water and pollution treatment, waste remediation and alternative energy

On the day CETA came into effect three years ago, 98.4% of tariffs on all non-agricultural Canadian goods entering the EU were eliminated. After seven years, 98.8% of these goods will be tariff-free. In response, Canada will remove 98% of its tariffs on the same goods coming from the EU. There are transition periods of three to seven years for ships, automotive products and certain agricultural goods in Canada, while poultry and eggs are excluded. Canadian import quotas on EU dairy products will rise, but the tariffs on such imports, above those quotas, will remain.

In the services sector, a “most-favoured-nation” treatment was applied, where all parties providing services in the EU and Canada are treated equally. There is no import quotas on services or service providers from other CETA nations. Business visitors without work permits are now allowed temporary entry for purposes of investment.

In addition, Canadian service companies no longer have to maintain a representative office in the EU, or be an EU resident, in order to supply services to EU customers. This has been especially helpful for smaller companies that lack the resources to establish permanent offices within the EU.

“The ability to temporarily locate employees in the EU makes it easier for Canadian companies to do business in, and with, Europe,” says Tapp. “This is especially so for smaller businesses that don’t have the resources to set up an office there.”

Finally, CETA covers government procurement. As a result, Canadian companies can now bid on EU procurement contracts, a three-trillion-euro (CAD$4.6 trillion) market. Europeans enjoy the same relationship and have access to Canadian government procurement contracts. This has led to increased competition here at home and, in the process, made Canadian businesses more competitive overall.

The intent of CETA is to foster the growth of Canadian companies that wish to expand their operations in Europe. A simpler regulatory environment, improved treatment of intellectual property and well-defined dispute processes has resulted in increased investment by Canadian firms keen to join EU supply chains.

“Canadian companies are increasingly using outward investments to reach foreign consumers directly in their home countries,” Tapp says.

The most-favoured-nation clause also applies to investments. This means that an EU country can’t require a Canadian investor to export or use a certain percentage of local content. Likewise, Canada can’t impose such restrictions on EU companies investing here.

In past research surveys, Canadian companies with foreign affiliates named cross-border regulatory hurdles as the top challenge to their foreign business. CETA’s provisions have eased much of this concern.

With the U.K. leaving the EU on Jan. 31, 2020, they’ve entered into a transition period, which will see the terms of CETA continuing to apply until Dec. 31, 2020. When this period ends, the U.K. will no longer be bound by the EU’s treaties with third countries, including CETA. Canada-U.K. bilateral trade would no longer benefit from any CETA preferences and would be based on World Trade Organization rules, including most-favoured nation tariffs on goods. The Government of Canada will continue to pay close attention to the U.K.-EU trade negotiations during this time and monitor how Canada’s trade with the U.K. may be affected.

According to the office of Mary Ng, Canada’s Minister of Small Business, Export Promotion and International Trade, officials from both countries are currently working toward a “transitional agreement” to minimize disruptions for businesses and workers. Meanwhile, according to reports, the U.K. is keen to finalize its trade terms with the EU and believes other trading partners now have enough clarity to proceed with their own deals. Any future trade agreement between Canada and the U.K. would be influenced by the U.K.-EU trade negotiations, as well as any unilateral U.K. approaches.