MyEDC account

Manage your finance and insurance services. Get access to export tools and expert insights.

Solutions

By product

By product

By product

By product

Insurance

Get short-term coverage for occasional exports

Maintain ongoing coverage for active exporters

See how portfolio credit insurance helped this Canadian innovator expand.

Guarantees

Increase borrowing power for exports

Free up cash tied to contracts

Protect profits from exchange risk

Unlock more working capital

Find out how access to working capital fueled their expansion.

Loans

Secure a loan for global expansion

Get financing for international customers

Access funding for capital-intensive projects

Find out how direct lending helped this snack brand go global.

Learn how a Canadian tech firm turns sustainability into global opportunity.

Investments

Get equity capital for strategic growth

By industry

Featured

See how Canadian cleantech firms are advancing global sustainability goals.

Build relationships with global buyers to help grow your international business.

Resources

Popular topics

Explore strategies to enter new markets

Understand trade tariffs and how to manage their impact

Learn ways to protect your business from uncertainty

Build stronger supply chains for reliable operation

Access tools and insights for agri-food exporters

Find market intelligence for mining and metals exporters

Get insights to drive sustainable innovation

Explore resources for infrastructure growth

Export stage

Discover practical tools for first-time exporters

Unlock strategies to manage risk and boost growth

Leverage insights and connections to scale worldwide

Learn how pricing strategies help you enter new markets, manage risk and attract customers.

Get expert insights and the latest economic trends to help guide your export strategy.

Trade intelligence

Track trade trends in Indo-Pacific

Uncover European market opportunities

Access insights on U.S. trade

Browse countries and markets

Get expert analysis on markets and trends

Discover stories shaping global trade

See what’s ahead for the world economy

Monitor shifting global market risks

Read exporters’ perspectives on global trade

Knowledge centre

Get answers to your export questions

Research foreign companies before doing business

Find trusted freight forwarders

Gain export skills with online courses

Discover resources for smarter exporting

Get insights and practical advice from leading experts

Listen to global trade stories

Learn how exporters are thriving worldwide

Explore export challenges and EDC solutions

About

Discover our story

See how we help exporters

Explore the companies we serve

Learn about our commitment to ESG

Understand our governance framework

See the results of our commitments

MyEDC account

Manage your finance and insurance services. Get access to export tools and expert insights.

The Country Risk Quarterly, a snapshot of 50 markets around the globe, is one of the most valuable tools produced by Export Development Canada (EDC) because it offers insights into a variety of risks for Canadian exporters and for those thinking of expanding their business beyond borders.

As country risk analysts, my colleagues and I are focused on the global economic and political risks of doing business in another country. For example, if your company is looking to sell machinery to Iraq, this guide helps you do your due diligence on whether you’ll get paid.

The interactive guide provides valuable insights on rapidly changing global markets, new opportunities and the latest political and economic risks that could affect your business.

While it’s less likely today that a government will fully expropriate a company’s assets or investments, government interference is the most predominant risk we rate. A government can target a company by adopting a series of measures that have the same effect as expropriation. For example, think of an incoming regime that cancels a key permit for a mine. This rating also gives exporters a better understanding of the business climate in a particular country since it includes indicators, like corruption, rule of law and the regulatory environment.

If government interference is sometimes difficult to pinpoint, political violence is more tangible to grasp. Unlike criminal violence, say from drug cartels, we’re measuring the likelihood of violent acts in a country that could either overthrow a government or change government policies. As an example, look at recent events in Ecuador, in which demonstrators attacked government offices to protest the elimination of a fuel subsidy.

Finally, rounding out the political risks section is transfer and conversion risk. Conversion restrictions include measures that prevent companies from converting local currency to hard currency (such as the U.S. dollar), while transfer restrictions are measures that inhibit the transfer of hard currency out of the country. A topical example would be Argentina, where, faced with economic and financial crisis, the government is implementing policies to reduce large outflows of foreign exchange.

In some emerging markets, the government or sovereign often play a significant role in the economy. For transactions that involve the state, our team produces a sovereign rating to measure the probability of non-payment. This rating combines the macroeconomic ability and willingness of a government to meet its payment obligations. For example, a country might have very low public debt, but has a history of payment arrears. It’s, therefore, a blend of economic and political risks. For example, we recently downgraded Nigeria’s sovereign rating due to its growing external debt, slow pace of structural reforms and growing security concerns.

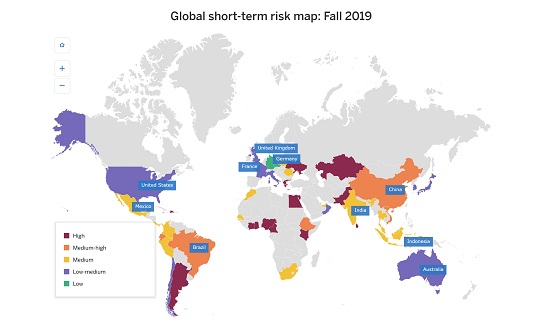

While these are all risks that have a medium- to long-term horizon, the short-term commercial rating we assign is based on a one-year forecast, which measures the average commercial default rate in a country.

The Country Risk Quarterly (CRQ), which we produce four times a year, is a way for you to follow short-term economic indicators—economic growth forecasts, exchange rate movements and the level of import cover—to get a better idea if there’s enough foreign currency in a market to get paid. Throughout the year, our analysts use in-house methodologies, data and expertise to rate all these risks. This valuable tool includes a risk-rating table, which summarizes the category of risk in that country.

Since the flip-side of risk is opportunity, the CRQ also provides exporters with an overview of the current bilateral trade relationship and how top industries in that country are performing. Being on top of these economic and political movements may help you adjust your business accordingly and to take on opportunities in these markets.

Understand how Incoterms FCA defines delivery, risk transfer and exporter responsibilities.

A 2026 update to EXW Incoterms, costs, delivery obligations and risk transfer explained.

A guide to Group C Incoterms, covering costs, insurance and risk transfer rules.

How population growth and investment needs are creating infrastructure opportunities in West Africa.

From homecooked meals to exotic global tastes, discover the key trends shaping the food industry